I started working with Quivira’s Carbon Ranch Initiative in August 2022 sharing a joint fellowship appointment with another non-profit organization, Point Blue Conservation Science. The Quivira Coalition and Point Blue Conservation Science are amongst a diverse global collaborative of over 60 organizations who partner with Wolfe’s Neck Center’s OpenTEAM project. OpenTEAM, or Open Technology Ecosystem for Agricultural Management, is a convener of agricultural producers (i.e. farmers, ranchers, land stewards, however someone identifies), researchers, scientists, engineers, farm service providers, policymakers, NGOs, etc., who work together as food systems leaders to help co-create an “equitable, accessible, and interoperable toolkit for universal access to agricultural knowledge and better soil health.”

OpenTEAM, Quivira Coalition, and Point Blue Conservation Science have given me the opportunity to work amongst many amazing minds doing important work in climate smart agriculture and building resilience on working lands. The fellowship has thus far allowed me to attend three incredible conferences: GOAT (Gathering for Open Agricultural Technology), Regenerate, and the IAC (Intertribal Agriculture Council) Conferences. I highly recommend all of these conferences. Please drop me a line if you want to learn more about any of them!

Making Connections

I want to share some insights from my experience at the IAC 2022 Conference with you, as this experience ties to Quivira’s Carbon Ranch Initiative work and what I’m learning in my fellowship.

As I was tabling over the three-day conference, I met wonderful people representing diverse Indigenous communities and their agricultural practices. Quivira asked me to bring some of its resources to share, as well as resources from Point Blue and OpenTEAM. Attending the event not only enhanced my understanding of the depth and breadth of Tribal agriculture, it also inspired me to reflect on some of the partnerships Quivira has developed with tribes in New Mexico and what we’re learning from them.

The Pueblo of Santa Ana is a leader and actively engaged in ecological restoration projects on their lands, empowering both their Department of Natural Resources and their Department of Agriculture to rewild and heal their watershed and native landscapes.

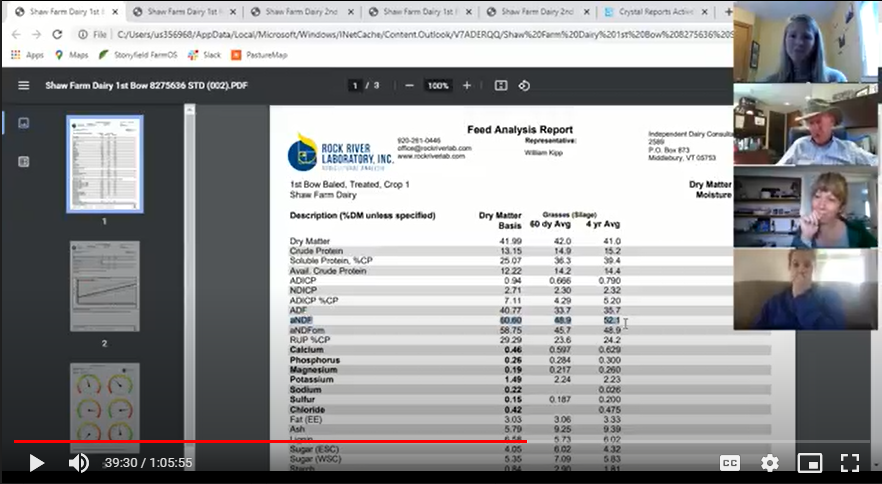

Starting in 2018, Santa Ana Pueblo was one of the first groups in New Mexico to implement compost on rangeland field trials. Two years later, Quivira initiated similar work. In Spring 2021, the Pueblo of Santa Ana and Quivira’s Carbon Ranch Initiative shared their findings about this research at an IAC virtual conference session (32:42 is when the “Resilient Ecosystems: Building and Restoring Soil Health” presentation by the Pueblo of Santa Ana begins.)

The former governor of Santa Ana Pueblo, Glenn Tenorio, currently works with the Pueblo’s Department of Natural Resources. He shared his experience over the years building relationships with working lands practitioners, such as Daniel Ginter, who has helped reintegrate livestock and restore native grasslands throughout Santa Ana Pueblo’s landscape. I highly recommend listening to Tenorio’s and Ginter’s interview on the “Down to Earth” podcast series from Spring 2022.

Land Care and Stewardship

Indigenous communities have been stewarding land in reciprocity with nature since time immemorial. The current Healthy Soil Principles that have become core tenets in regenerative agriculture practices are not new concepts; the wisdom has existed since the beginning of agriculture and has been practiced by Indigenous communities for thousands of years.

The Carbon Ranch Initiative has been working on an exciting project with Mad Agriculture and has co-developed a training workbook for Quivira’s Planning Program. The Soil Health Planning curriculum will be introduced in upcoming webinars, so be on the lookout for exciting opportunities to participate and learn more about the program!

After attending the IAC Conference, I learned more about producer’s needs and interests which offered insights into what is helpful to include in the Soil Health Planning curriculum. Through Quivira’s approach of outreach, education, and research, our organization offers many opportunities to strengthen existing partnerships and engage with a diverse network of planners and producers who want to learn more about creating soil health plans. I am excited to continue building these relationships as I continue working with the Carbon Ranch Initiative in 2023!

This blog post was originally written for Quivira Coalition’s In The Field Newsletter.